Rethinking AI sovereignty

Why “owning the stack” is the wrong goal for most organisations

AI sovereignty is often discussed as if the goal is straightforward: build domestic compute, secure chips, own data centres, run your own models, and keep everything inside a controlled perimeter.

That instinct is understandable but it’s also a fast way to spend a lot of money while remaining dependent on someone else.

A recent World Economic Forum collaboration with Bain & Company pushes a more useful framing: sovereignty is not rigid self-sufficiency. It is strategic control and resilience achieved through focused local investments plus trusted collaboration across the ecosystem.

Cathy Li captures the shift cleanly: AI is no longer a set of isolated technologies. It is becoming an interconnected system where compute depends on energy, infrastructure depends on long-term capital, and scale depends on partnerships. Weakness in one layer limits the whole.

This article takes that systems view and translates it into enterprise reality: what AI sovereignty means when budgets are finite, regulation is real, operations cross borders, and data cannot simply be “handed over” to tools you do not control. It outlines the practical trade-offs behind the concept and closes with a concise checklist you can use to pressure-test your own AI strategy.

The problem with the “arms race” framing

When AI sovereignty is framed as an arms race, the implied question is simple: who can build the most compute, secure the most chips, and deploy the biggest data centres the fastest?

That framing turns AI into a procurement contest. And that is precisely where it breaks down.

AI no longer behaves like a standalone technology that can be “won” by owning a single layer. It functions as a tightly coupled system, where success depends on how multiple constraints interact over time. Compute capacity only delivers value if energy is available and affordable. Infrastructure only scales if long-term capital, permitting, and grid access align. And real deployment at scale depends on partnerships across suppliers, operators, and application ecosystems.

In this context, adding more GPUs does not automatically increase capability. It can just as easily create new bottlenecks elsewhere in the system. Energy becomes the limiter. Permitting slows expansion. Vendor dependencies harden. Costs compound without improving control.

This is why the arms race framing is misleading. It suggests that scale alone produces advantage, when in reality advantage comes from system alignment. Without that alignment, AI adoption risks becoming an expensive accumulation of assets rather than a durable, governable capability.

Sovereignty in practice is control, not ownership

If scale alone does not produce durable advantage, then sovereignty cannot be defined by how much infrastructure you own.

It has to be defined by what you can control.

The most useful way to interpret AI sovereignty is therefore not as self-sufficiency, but as the ability to shape and govern AI in line with your obligations and values, while retaining operational control, flexibility, and resilience over time.

In that framing, ownership is secondary. Control and resilience are the goal. Collaboration is not a compromise; it is part of the model.

This is also why AI sovereignty now matters at enterprise level, not just national level. If you operate across regions, your AI deployments must survive legal change, vendor change, pricing change, and model change without forcing you to rebuild your systems or surrender control each time something shifts.

Scale alone has not delivered durable advantage

Once sovereignty is understood as control rather than ownership, a second implication becomes unavoidable: scale on its own is not a strategy.

Investment in AI infrastructure is enormous, yet durable advantage remains concentrated among a small number of players. Most economies – and most firms – cannot replicate full-stack capability across every layer of the AI value chain, nor would doing so automatically increase their level of control.

For everyone else, the winning approach looks different. It is not about owning more assets, but about making deliberate choices about where to build real strength, where to partner, and how to keep the system governable over time.

This means the winning approach for most organisations is:

- Focus investment where you can build genuine strength,

- Avoid scattered attempts to own everything

- Partner deliberately to fill gaps, and

- Make sure the seams between partners remain interoperable.

In plain language: stop trying to own the whole stack. Start designing for control.

Translating AI sovereignty into enterprise decisions

Once you stop treating AI sovereignty as an ownership problem, the question stops being “what should we build?” and becomes “what must we be able to control?”

For most companies, sovereignty is not a geopolitical posture but an operational necessity.

It matters for three practical reasons:

-

Risk management

Unmanaged AI use creates regulatory, contractual, and reputational exposure—especially when sensitive or regulated data is involved. -

Continuity and leverage

If your AI capability depends on a single vendor’s pricing, roadmap, availability, or policy stance, you have dependency, not a strategy. -

Value capture

Data, workflows, and knowledge assets generate long-term advantage only if the organisation retains control over how they are used, reused, and evolved. When those assets leak into tools that cannot be governed, the value leaks with them.

Taken together, these pressures point to a clear enterprise definition of AI sovereignty:

The ability to deploy and govern AI in line with organisational obligations and policies, while retaining operational control, portability, and auditability through a mix of internal capability and trusted partners.

That definition matters because it turns a vague buzzword into something actionable. In practice, it translates into five concrete capabilities.

Capability 1:

Control the data plane

- Where does sensitive data live?

- Where is it processed?

- What is logged, retained, and shared?

- Can you demonstrate lineage and access control?

Capability 2:

Control the model plane

If your architecture assumes a single model, you inherit that model’s:

- cost structure,

- regional availability,

- governance constraints,

- and failure modes.

Capability 3:

Build for interoperability and workload portability

Control without portability is fragile.

Interoperability and workload portability are how organisations avoid lock-in across clouds, data centres, and edge environments. In practical terms, this comes down to resilience:

- Can you exit without a rebuild?

- Can you move workloads as legal or procurement realities change?

- Can you keep operating if a vendor’s priorities shift?

Capability 4:

Auditability by design

In regulated environments, “trust me” is not governance.

You need to be able to explain, consistently and defensibly:

- what data influenced an output,

- which model produced it,

- what transformations occurred,

- who approved it,

- and what changed over time.

Capability 5:

Partnerships treated as infrastructure

AI systems do not stop at organisational boundaries. Partnerships are part of the system.

They should be selected and governed like critical infrastructure decisions, because they determine:

- what you can control,

- what you can prove,

- and how quickly you can adapt when the world changes.

At this point, the pattern should be clear.

AI sovereignty at enterprise level is not achieved by buying more infrastructure or picking the “right” vendor. It is achieved by designing an AI operating model where data, models, workflows, and partners remain governable over time.

The question then becomes practical rather than conceptual:

Where do you enforce that control in real systems, with real data, across real borders?

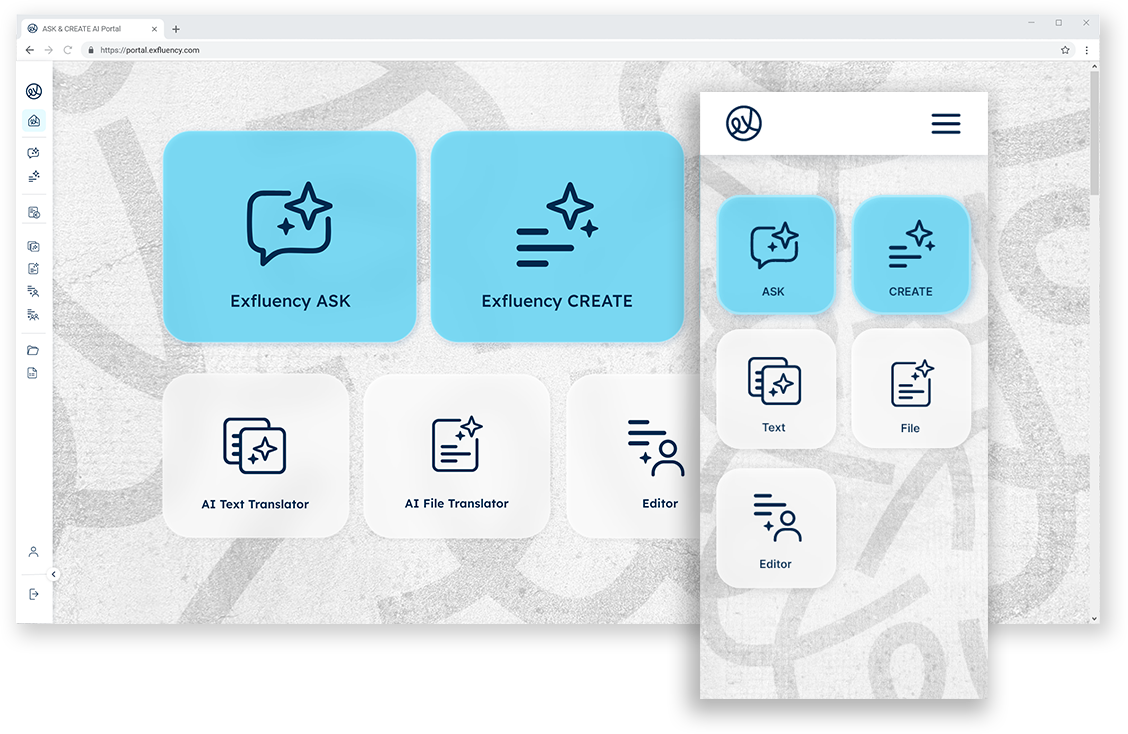

Exfluency’s angle: sovereignty as operational control

Exfluency’s work sits squarely inside the constraints described throughout this article: multilingual enterprise content, cross-border operations, and security and compliance requirements that make consumer-style AI patterns unacceptable.

In that environment, AI sovereignty is not an ambition but an architectural requirement.

Rather than pursuing full-stack ownership, Exfluency focuses on where control actually needs to exist in enterprise AI systems.

1. Model choice without architectural lock-in

In many enterprise AI setups, “model choice” is theoretical. The architecture quietly assumes one provider, one API, one roadmap.

Exfluency treats model optionality as a system property. Language models are selected based on policy, risk profile, data sensitivity, and performance needs – and can be switched without rebuilding workflows or re-ingesting data.

This matters because model risk is not static. Cost, availability, regulatory exposure, and acceptable use policies change. Sovereignty increases when those changes do not force a redesign.

2. Multilingual data that remains governable

Most enterprise AI conversations implicitly assume monolingual data. In reality, regulated organisations operate across languages, jurisdictions, and documentation regimes.

Exfluency is built around multilingual enterprise data flows where:

- enterprise data flows where: source material cannot be freely shared,

- transformations must be traceable,

- and outputs may carry legal or operational consequences.

Sovereignty here means knowing where data flows, how it is transformed, and which systems and humans touched it, regardless of language.

3. Provenance and integrity at the knowledge layer

For enterprises, the risk is rarely just hallucination. It is loss of trust in the underlying knowledge base.

Exfluency’s three-chain approach is designed to make knowledge assets:

- verifiable,

- auditable,

- and defensible over time.

This is not about “blockchain for security”. It is about being able to demonstrate provenance, integrity, and accountability for content that feeds AI systems – especially when that content informs decisions, documentation, or regulated outputs.

4. Designing out dead ends before they appear

Many AI initiatives fail quietly, not because they never worked, but because they became impossible to evolve.

Exfluency deliberately designs for:

- portability of workflows,

- interoperability between components,

- and clean exit paths from models or providers.

This reduces lock-in not as a negotiating tactic, but as a resilience measure. Sovereignty that disappears the moment conditions change is not sovereignty.

What this adds up to

Taken together, the sections above point to a simple conclusion: for enterprises, AI sovereignty is not something you declare. It is something you design for, test, and continuously reassess.

The difference between a “sovereign” and a fragile AI setup is rarely ideological. It shows up in concrete choices about data handling, model dependency, portability, auditability, and partnerships. And in whether those choices are explicit or accidental.

If sovereignty is really about control, resilience, and accountability, then it should be possible to examine an AI setup and see where those properties are strong, where they are weak, and where trade-offs have been made, consciously or not.

The most direct way to do that is to ask a small number of practical questions and take the answers seriously. Not as a scorecard, but as a map of where control exists and where it does not.

A simple sovereignty checklist for enterprise leaders

Use this as a diagnostic checklist for procurement and system design. The purpose is not to “pass”, but to make trade-offs and gaps visible.

Your answers may well be “no” today. That does not mean failure. It means clarity.

What matters is whether you can see, and consciously decide on, where control exists, where it does not, and where that is acceptable.

Sovereignty checklist

Data

- Can we prove where sensitive data lives and how it is processed?

- Are we leaking data via tools we cannot govern?

- Do we have clear rules for logging, retention, and access?

Models

- Can we change models without rebuilding workflows?

- Do we have a model policy by risk class and use case?

- Can we justify why a given model is allowed for a given task?

Portability

- Can we move workloads across environments as legal or commercial realities change?

- Can we export knowledge assets, prompts, and outputs in a usable form?

- Can we exit a vendor without losing operational capability?

Audit

- Can we explain outputs end-to-end, including data lineage and human approvals?

- Do our audit logs survive scrutiny, not just internal demos?

Partnerships

- Which layers must we own for control?

- Which layers can we source safely through trusted alliances?

- Are partnership seams designed to stay interoperable over time?

This checklist does not tell you whether you are “sovereign” or not.

It shows you where sovereignty exists, where it is weak, and where you are implicitly relying on trust, vendors, or assumptions. From there, sovereignty becomes a set of conscious design choices, not a label.

If you want support at that point, there are two sensible next steps, depending on what you need.

If the questions surfaced uncertainty or disagreement internally:

Exfluency works with organisations in an advisory capacity to help teams answer these questions properly, map trade-offs, and clarify what level of control is actually required for their context.

If the answers revealed gaps you are not comfortable with:

Exfluency’s systems are designed to address exactly these problem areas. Our Sales team can help you assess whether Exfluency is a good fit for your organisation and your constraints before any technical commitments are made.

Either way, the objective is the same: to move from implicit assumptions to deliberate design.